For the first time, researchers have found a cost-effective and convenient way to apply a silver-based antimicrobial clear coating to new or existing textiles. Their method uses polyphenols, commonly found in food items notorious for staining clothes such as wine and chocolate. A range of textile types can be treated by the researchers’ method, and items can be washed multiple times without losing the antimicrobial and therefore anti-odor property.

It may be winter for half the world right now, but before too long the warm weather will return, bringing with it beach trips, ice cream, insect bites, and of course, sweat. There are many kinds of products that can be worn or applied to the body which aim to reduce body odor, but these often come with a compromise such as expense, breathability, limited choice, or something else. Some of these make use of silver, which is well known for its antimicrobial properties, but can be difficult to apply to things like clothes in an easy and efficient way.

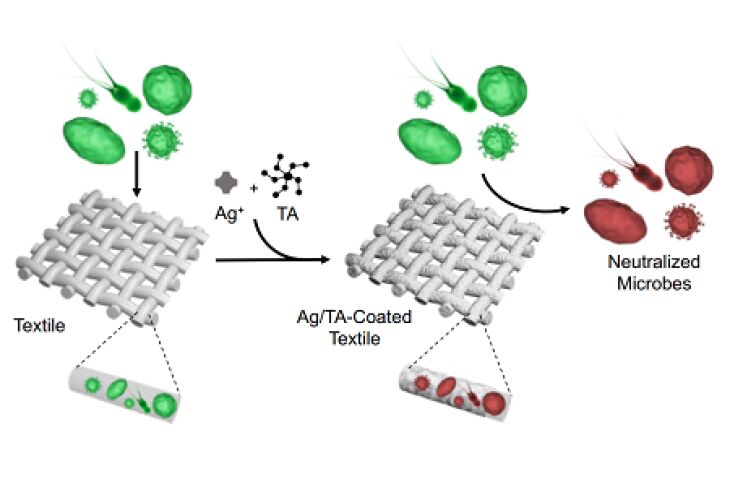

A team led by researchers from the University of Tokyo’s Graduate School of Engineering has pioneered a way to apply an antimicrobial silver coating to textiles that is cost effective, simple and has some useful implications too. They essentially used a compound known as a polyphenol, tannic acid (TA) specifically, to bind silver (Ag) to fabrics. Polyphenols are found in chocolate and red wine amongst other things, and are responsible for their infamous ability to stain clothing and tablecloths. Fortunately, the researchers’ coating, called Ag/TA, is completely clear so it doesn’t discolor textiles, but best of all, it can survive being washed.

“As kids often do, my son stained his shirt with chocolate one day, and I couldn’t scrub it out,” said postdoctoral fellow Joseph Richardson. “Associate Professor Hirotaka Ejima and I have studied polyphenols for over a decade, but this chocolate incident got me thinking about using tannic acid to bind silver to fabrics. We think we’ve found two methods to apply our antimicrobial silver coating to textiles, suitable for different use cases.”

The first method might be useful for commercial clothing or fabric producers. Textiles can simply be bathed in a mixture of the silver compound and the polyphenol binder. Another method, perhaps more suited to small-scale settings, including the home, is to spray items of clothing, first with the silver compound and then with the polyphenol binder. An obvious advantage is that people can add the coating to existing items of clothing.

“But what’s most exciting is not the ease of application, but how effective the coating is,” said Richardson. “We wanted to study the effect of the antimicrobial coating not just on odor-causing bacteria, but also on fungi and pathogens like viruses. With so many variables to control, it was a challenge of time and complexity to test variations of compounds against variations of microorganisms. But through carefully optimizing our testing methods, we found that the coating neutralizes everything we tested it on. So Ag/TA could be useful in hospitals and other ideally sterile environments.”

The binding power of TA is so strong that coated textiles tested by the researchers like cotton, polyester and even silk, maintain antimicrobial and anti-odor properties for at least 10 washes.

“This isn’t just a hypothetical situation limited to the lab, I’ve tried it on my own shirts, socks, shoes, even my bathmat,” said Richardson. “We’d like to see what other useful compounds polyphenols might help bind to fabrics. Antimicrobial silver might just be the start.”